Sobriquet 37.4

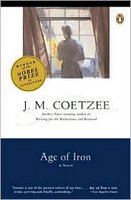

Given the difficulty I had focusing yesterday, I was not sure how long it would take me to completethe rather modest reading I assigned myself last night. Having struggled to harness my hyperactive mind while re-reading Age of Iron

Given the difficulty I had focusing yesterday, I was not sure how long it would take me to completethe rather modest reading I assigned myself last night. Having struggled to harness my hyperactive mind while re-reading Age of IronHaving read Age of Iron twice now, and having recently read Elizabeth Costello and re-read both Slow Man and Disgrace, I can say that, of all the Coetzee I have read, this novel is the one I find least engrossing. I do not know whether it is a matter of my difficulty relating to the subject of the book, but I simply could not feel Coetzee's story as viscerally as I do his later work. To be honest, though, I imagine my position as an American who has never visited the South Africa Coetzee describes in Age of Iron has a lot to do with my reaction. I have vague memories of learning about apartheid in grade school but, just as my memories of a bifurcated Germany have dissolved into little more than a knowledge of a historical fact after the Berlin Wall crumbled into pieces small enough to sell to tourists, my sense of racial segregation in South Africa has been dulled by images of a grinning Nelson Mandela vigorously shaking hands with F. W. de Klerk on the covers of countless newsweeklies.

To an extent, I suppose, I can try to draw upon my own experience with racial tension in my own country to attempt to understand some of the novel's more salient episodes, but if I cannot understand the depth and complexity of the racial struggles that tore through my own culture a quarter century prior to my birth, I cannot imagine how I can truly grasp the struggles of South Africans in the middle-to-late 1980s. In fact, I think it would be presumptuous for me to say that I "get" anything of the sort. In other words, my historical situation barring me from the ability to emphathize with South Africans fighting the effects of apartheid, the best I can muster is a dulled, over-intellectualized sympathy. And, it would seem, that is not enough for me to enjoy the novel.

That said, I do feel Age of Iron is as typically thoughtful a book as one would expect from a writer of Coetzee's caliber. Through her musings on death, disease, race relations, and (meta)physical isolation, Mrs. Curren establishes herself as one of the author's more appealing creations, and one that marks a turning point in the author's career. In her, we find David Lurie's brooding fixation on physical decline, Elizabeth Costello's struggle to connect with her children, and Paul Rayment's dogged attempts to preserve both dignity and history in the face of inevitable, indelible dissolution.

I refuse to say Age of Iron does not equal, say, Disgrace in terms of quality, but I do suspect its audience will not be as broad for as long a period of time as that of the latter novel or even of Slow Man. Put simply, Age of Iron is the type of novel I imagine a History teacher might include in a course on apartheid, the sort of literary work that illuminates and adds dimension to a dry historical textbook, but not a book one would find as universally accessible as Disgrace, Slow Man, or Waiting for the Barbarians. But, then again, I don't suppose Coetzee was trying to write anything other than what he wrote--namely a book that captures a particular mood of a particular type of person living in a particular place at a particular time. And that, too, I would argue, is as important as any literary endeavor, if not as appealing.

Note: I welcome any and all comments about what I have written; I would love to discuss the nuances of this book with fellow fans of Coetzee.

For tomorrow: Depending on the weather, I would like to make the trek to the university library to collect secondary materials on Coetzee, with a focus on Age of Iron. In terms of reading, I will again be fairly conservative and assign myself--bearing in mind the piles of grading and hours of driving--one critical article.

Thanks for reading and thanks for the moral support you've all been giving me!

Comments